Words & Pictures

Like my dad, I have a passion for words and pictures. One of my fondest memories is sitting with him at the kitchen table drawing. I remember making a man in a hat. Like most children I drew the hat like a cake on a platter, perched on a circle, but he showed me—first with his own hat, then in a diagram—how the hat rests down over the ears. I was about four and felt very grownup when he told me that.

Another lesson involved drawing the house behind us—a three-story white shingled house. I was caught up in drawing every shingle, wondering how I would ever finish, and the drawing kept getting worse and worse. You should suggest, said my dad. He showed me how a few horizontals attached to short verticals could imply an entire wall. Magical.

He also taught me about words. How much fun they could be. There were long poems he recited from memory that he’d written himself. One, “The Tale of the Bald King” begins,

Far away where no one visits

Lies the land of Whatsitisits.

The Whatsits are a gentle race

Who wear long whiskers on their face.

They let them grow beyond their knees

For if they didn’t they’d jollywell freeze.

And then there were the songs he’d written, “The Chocolate Soldier Brigade,” “Little Ragged Ann”—he would sing them every so often, usually on a Saturday, or driving down the road. I have the sheet music he had made, copyright 1939 in San Francisco. Later I discovered they were part of a children’s musical he’d written and sent off to Walt Disney. Disney said he developed everything "in house" and my dad never sent it out again. But every few years my mother would record a professional singing the songs—usually a friend of the family—and present the tape as a Christmas present.

Storytelling was prized at our house, and at the dinner table my two sisters and I would recount the eccentricities of our teachers, sometimes pushing off from the table to demonstrate a walk or a gesture. My mother, an especially good mimic, would join in with stories from her office, letting her glasses drop down her nose for one speaker, pushing them up for another, altering her voice as she described the daily affairs. She was head of personnel for United Dairy Farmers, a large chain in southern Ohio, and we all thought her office must be the most exciting place in the world. My sister Jane spent a day at work with her, but when she came home she whispered, “Nothing happens.”

We realized it was all in the telling.

Pictures and words. Words and pictures. I had a wonderful English teacher in high school, Miss Catherine Morrison. One of our assignments was to write a book report on a children’s book. I chose Alice in Wonderland. I was a freshman and hadn’t read Alice since 2nd grade, when my mother had given me the book for Christmas. It had scared me to death, falling down a deep hole passing jars of marmalade, and then changing sizes. Plus all the strange characters. But as scary as it was, I wanted to go back to it. This time I found it hysterically funny. And I wrote a story, afterward, about riding a backwards bicycle. Miss Morrison liked it. While she was a demon for verb conjugations and sentence diagramming (she would sometimes back off from an especially elaborate sentence diagram someone had put on the board and gasp in awe over the beauty of it) she liked creativity. We wrote parodies, plays, commercials, an autobiography, and if we were assigned to write certain types of sentences as exercises, she encouraged us to make them amusing.

In college I majored in art and entered the Mademoiselle guest editor contest. I wrote and illustrated a series of ads on the Revolutionary War. It was such fun putting the two together, words and pictures. I received a note from one of the judges (I was a semi-finalist) on how well my words worked with my pictures—a rare talent she said, though it would be years before I would publish a picture book.

I was first a junior executive at a San Francisco department store.

Then I designed clothes at a shop on Union Street.

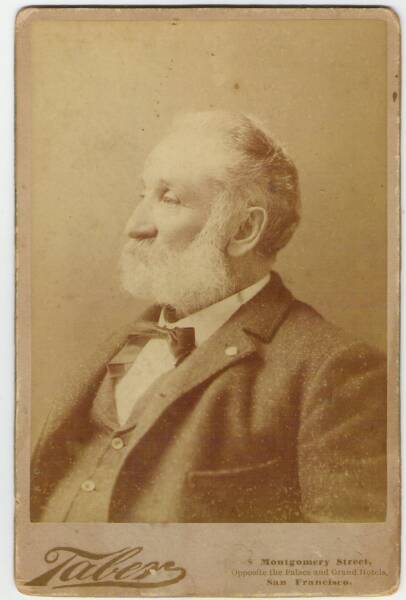

During this time, I kept company with my aunts Mabel and Martha, who filled me in on family history: my sea captain ancestors who sailed round the Horn from Maine and Philadelphia to San Francisco; my grandfather, an artist, who also played viola and conducted an orchestra; my great, great uncle, Frank M. Pixley, who founded, in 1877, published and edited the San Francisco Argonaut.

No wonder my father loved words. No wonder he loved pictures. No wonder he wrote songs. Oddly, he’d never discussed his family history—my mother said it was because he was a change-of-life baby, and having been around older people all his life, he had an aversion to history.

But I began reading the historical columns in the San Francisco Chronicle, and learned that Pixley hired Ambrose Bierce for his first editor, that he drove his mule team down Van Ness Avenue each night after putting the magazine to rest, that he was asked to give the Fourth of July speech at Union Square, that he was a confidant of Mark Twain.

I was born in Missouri. I had always loved Huckleberry Finn. A web began to form in my head of destinations and possibilities. An urge to make something. I wasn't sure what, but the means I knew would be pictures and words.

Sandra Dutton has published seven books for children, the latest from SwanHorse Press imprint of Monte Ceceri Publishers. Dutton has an A.B. in Fine Arts and a Ph.D. in Rhetoric & Composition, and has taught English at the University of Louisville, New York Institute of Technology, and the University of Maine, Farmington. She now teaches creative writing in the graduate program at Southern New Hampshire University and research writing at Excelsior University. She was the founder, in 1982, publisher and editor of her own literary magazine, River City Review, in Louisville, Kentucky. Her musical, Just a Matter of Time, was most recently produced at Bridge Street Theatre in Catskill, New York. Dutton is now working on several projects. She and her husband have four grown sons, eight grandchildren, and now live in Savannah, Georgia.

If you would like to learn more about Sandra Dutton, you can visit Bold Journey.

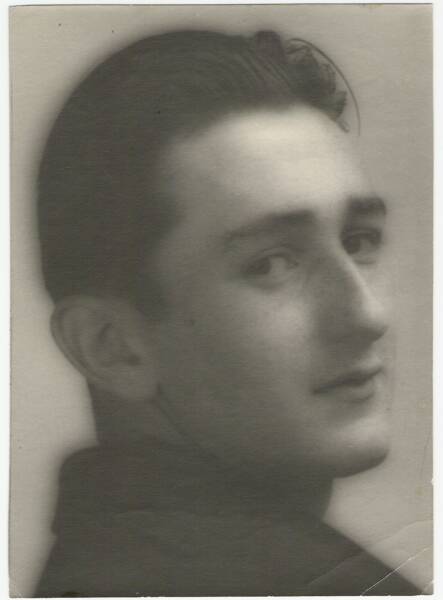

My Dad, Henry H. Hipkins, in his 20s

Frank M. Pixley, Founder, Publisher & Editor

of the San Francisco Argonaut

Sandra Dutton, Age 4, Riding Uncle Harry

The Castro Valley Kids, Sandra on the Right